Post 2: DCMJ: Mom's Stories

Note 1: This chapter, as its own separate unit, didn’t make the final cut of the memoir, but I'm posting it here for a few reasons. I have a deep attachment to the stories Mom told me about her childhood, youth, and the early years of her marriage to my father, stories that strum with tension. And, as mentioned below, they provide additional context for you, either now or later, on her life and the circumstances I was born into. The first actual chapter of the memoir is included in Post 3: DCMJ: Chapter 1: The House on South Seventh Street.

Note 2: I’ve changed most of the names of non-family members—in this post and in the final version of the memoir.

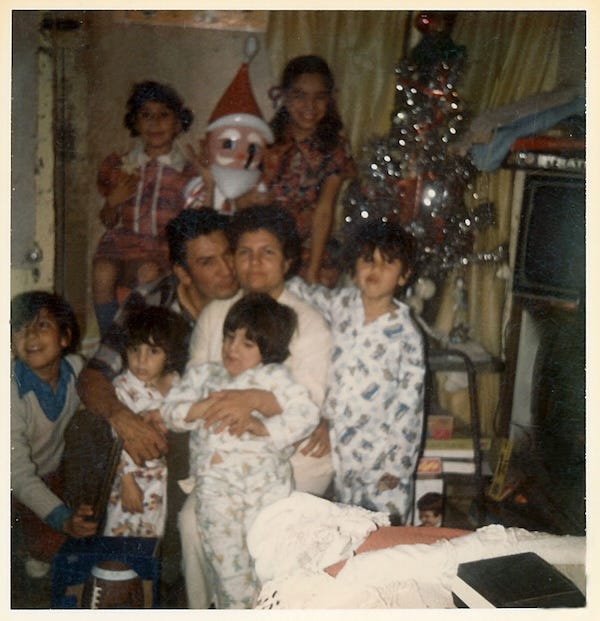

Note 3: I couldn’t help interspersing a few old family photos I love. The credit goes to my sister María R. Olivas for preserving them by scanning and retouching.

Mom’s Stories

I was hungry for stories, stories about my mother’s life before I was born, as if I couldn’t stand that she had lived parts of it without me. I must have been ten or eleven when I first begged for them on a hot summer afternoon in the living room of our housing project unit. Mom lay on her stomach on our torn-up couch as I kneaded the muscles in her shoulders and back, relieving her aches from cleaning white people’s houses. “Tell me about when you were a kid.” For the rest of my vacation from school, she took me back there, often mumbling the beginnings of anecdotes before drifting off to sleep, leaving me starving for more until she finally woke from her nap and finished them for me. That unleashed a barrage of questions from me and more stories from her, especially after the events took a dark turn, which they quickly did.

As much as most of Mom’s stories tortured me, I grew as addicted to them as she did to my small but strong hands. In the years that followed, my fingers unlocked more of them or the repetition of previous ones, all of which lived vividly in my imagination, as if I had experienced them myself. That’s likely what planted the seeds for the writing of this book, as I always envisioned it as a traditional biography about my mother. But the narrative took on a life of its own and morphed into a memoir about the evolution of our relationship--from my fierce attachment to her, to our painful rift, to the birth of a separate self, all of it suffused by a nagging yearning to be loved completely.

And yet those early stories, stories I’ve come to treasure even more after Mom’s death in 2021, still have an important place in my sharing parts of my journey, as they prelude very well the family dynamics I was born into, along with fleshing out the most influential woman in my life, that quintessential survivor who repeatedly rose from the proverbial ashes.

My mother, Luciana P. Leyva, was born on September 11th, 1939 in the rugged West Texas town of Alpine, where she grew up the second of ten children and later raised her own ten kids. Compared to the rest of the sparsely populated Big Bend Region, this hilly, desert community is hopping. Its official website boasts of a myriad of eateries, shops, and small local art galleries. You can earn a college degree there (at Sul Ross State University) or get treatment for a medical emergency (at the Big Bend Regional Medical Center). But, in the end, only about 6,000 people live there.

Alpine was heavily segregated when Mom was a kid with the Southern Pacific Railway, as it was known back then, dividing the town. White folks lived in the north side and Mexican-Americans in the south. Each community had its own grocery stores and schools, with the exception of the high school, which had already been integrated by the early 50s when Mom entered the ninth grade. Although the cemetery was located on the south side, off of the dirt road leading to the town’s landfill, even it was segregated. Latinos were buried at Holy Angels Cemetery and white folks at the adjacent, more manicured Elm’s Grove. They still are, for the most part.

To shop at grocery stores with lower prices and greater selection, Latinos had to cross the tracks, which could lead to conflicts. Older white boys at various crossing points threw hands-full of rocks at invaders. “Stay on your side of the tracks, you dirty Mexicans!” they’d yell. It infuriated Mom. While the rest of the family felt too intimidated to venture into the north side of town, she, still a grade-school kid then, volunteered to run her mother’s errands. “The stupid gringos didn’t scare me,” she said. Various times she crossed with her own handful of rocks.

“Did you ever get hit?” I asked her.

“I don’t remember getting hit,” she said. “If I did, it probably didn’t hurt, I was so mad.”

Although no one in Alpine cared about the distinction back then, Mom and her nuclear family weren’t technically Mexican, meaning that she and her siblings were all born in Alpine. So were her parents (Amá and Apá) and both set of grandparents, with the exception of her paternal grandfather who immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico as a young adult.

Mom and her older sister, Celia, didn’t have stereotypical Mexican features either. Taking after Apa’s side of the family, they looked like little gringuitas, with their fair skin, light brown hair, and green eyes. Strangers often mistook them for white girls. When their mother did cross the tracks with her two toddler daughters, for example, white ladies glared at her. One of them walked right up to her and accused her of stealing the girls. “Who do these girls really belong to, you lying Mexican?” she asked her. “Do you want me to call the police?” The confrontation terrified Amá. She rushed back home as soon as the woman finally backed off.

A normal response by Amá, given the climate of the time, although Mom would have reacted radically different in Amá’s shoes. Despite her small size, Mom was spunky and fearless from the beginning. She stood up to anyone, not just in response to the town’s racism and not only for herself but other family members as well. As a grade-school-aged kid, she’d smack girls on the playground at school to defend her older sister, and at home, she’d scream at her father to protect her mother from his beatings.

Apá regularly beat Amá. He’d slap and punch her and take her out to nearby fields at knifepoint in the middle of the night to batter her some more. Mom always woke to the sounds of it. She’d jump out of bed and scramble to find them, then tug at Apá to pull him off of her mother. Once, she intercepted a slap meant for Amá, which nearly knocked her out cold, but the next night, she was at it again, trying to protect her mother. “No way was I going to let Apá hurt Amá,” she told me.

Apá hadn’t always been abusive. He got along well with his wife before being drafted into the army during World War II, Mom said. She had fond memories of her parents socializing in their front yard with family or friends. A loving, attentive dad at first, Apá also played with his children. He’d pretend to be his kids’ pony and gave them rides around the living room. But after his medical discharge, he returned a changed man, violent toward his wife and cold and distant toward everyone else. He ramped up his drinking then, too—to manage his pain, Mom suspected.

Mom blamed this change on the misreporting by his military superiors of a death in the family back home. Misreading the telegram, they told him his wife, rather than his infant son, had died. They corrected their error later, but by then, Apá had suffered a nervous breakdown. He was discharged and sent to a mental hospital in the West Texas city of Big Spring and then home. Ironically, the mistaken news that he had lost the love of his life led to his almost killing her once he returned home.

Despite his psychological struggles, Apá remained focused on earning a living. For years, he worked as a mechanic in a local shop in town, until it was sold and Apá was let go. Struggling to find work after that, he moved the family out west to a suburb of El Paso called Escarate, and then Yselta, where Mom completed her seventh and eighth grade years at an integrated school. To help make ends meet, Apá put his older girls to work out there, picking cotton, which Mom hated. To speed up the process, she’d yank the full plant, stem and all, out of the soil and shove it into the plastic bag. As soon as Apá took off to run errands, she’d take a break to eat watermelon, then sing Mexican rancheras at the top of her lungs, a passion she’d indulge in for the rest of her life.

In Ysleta, the family’s financial situation improved, but the tension between Amá and Apá worsened, due to Apá’s continued drinking and philandering. One afternoon, Mom caught Apá escorting a mistress into his car outside a neighborhood bar, which drove her into a rage. She charged toward them with a handful of rocks, screaming “Get her out, Apá!” Apá yelled at her to get herself home and sped off. Mom ran after them, hurling her rocks, then rushed home to tell Amá. All of it led to more fighting between her parents and more beatings for Amá, until Amá finally called her father back in Alpine and asked him to drive her and her kids back to their hometown. After a few days, Apá followed and moved back in with his family.

By the beginning of the ninth grade, Mom was fed up with a fighting that seemed to have no end in sight. One night she snapped after Apá exploded at Amá again. After he pounced on Amá and began to strangle her, Mom grabbed a bat and struck him in the back. It shocked her parents into silence. Horrified herself, Mom dropped the bat and screamed, “Look what you made me do, Apá!” She stormed out of the house and, later that evening, moved in with her maternal grandparents.

“I never had it so good,” she told me. She had gone from the horrors of her homelife to peace, calm, and even fun at her grandparents’ place. Welito and Welita Magallanez lavished her with attention and gifts, buying her nice stationary for writing letters along with expensive “Evening in Paris” perfume and stylish hats and dresses for Sunday Mass. After services, Welito taught Mom to dance to Mexican rancheras. He also taught her to drive his old Chevrolet pick-up truck, which didn’t go very well at first. She stomped on the brake, jerking Welito forward, and ran over plants and other items in the yard. It prompted Welito to yell at her. “Why are you yelling?” she’d tell him. “That’s how you drive when you come home drunk.”

The most important lesson she learned from her grandfather was respect and care for the elderly. If Welito had a visitor, Mom had to serve them a drink and wait by their side with her arms crossed until they finished and then return the glass to the kitchen. She and Welito also did chores for the seniors in the neighborhood. Welito chopped up wood for them while Mom did their grocery shopping or picked up their mail at the post office downtown.

As much as Welito pampered his granddaughter, he was extremely strict when it came to boys. It infuriated Welito that a boy in her grade named Rudy kept calling the local radio station at night to dedicate songs to her and asked her out via the airwaves. He forbade Mom from accepting, and after spotting her talking to him in town at one point, scolded her severely. “We were just talking!” she told me, shaking her head, still visibly outraged all those decades later.

That rigidity made it easier for Mom to return home after Amá begged her to. Apá’s drinking had gotten worse, and although he continued to work, he barely supported the family anymore. Amá needed her daughter’s help, financially and in taking care of the kids. Mom helped her with both, after Apá made Mom quit school at the beginning of her sophomore year. He didn’t have any money to pay for school supplies and other nonsense, he told her. She needed to stop wasting her time at that place and get a job. She complied, feeling an obligation to help Amá as best she could.

After cleaning houses and working at a soda fountain for a short period, Mom landed a job at Hunter’s Photography Studio, a white-owned business on the north side of town. Mr. Hunter, the sixty-something owner, had a thing for Latinas, it turned out. He had had an affair with the Latina woman Mom had replaced. Shortly after hiring Mom, he made a pass at her too. He followed the pretty and petite seventeen-year-old into the darkroom and began caressing her shoulder as she worked, but Mom swatted his hand hard and rushed out of the room to take care of tasks in another part of the studio. Anytime they entered the darkroom together after that, Mom’s whole body tightened at the possibility her boss would try it again, but he never did. He must’ve sensed he’d have a full fight on his hands, and he probably valued Mom too much as an employee to scare her off.

Mom became fully skilled at taking customers’ orders, shooting portraits, and developing film. It impressed Mr. Hunter so much that he entrusted her with additional responsibilities and spent less time in the studio. Within a few months, he had his eyes set on retirement and planned to leave Mom to manage the business. Despite the unwelcomed incident in the darkroom, Mom loved her job. She loved her duties and the fact that she earned enough money to help Amá buy groceries and clothes for Mom’s younger siblings. She also began to develop a sense of professional purpose.

But then she met my father, Zacarias Olivas Jr., a handsome, very masculine man ten years her senior, a man my siblings and I referred to as Tata. (The Spanish word for “dad” in some Latino communities.) They got to know each other while serving as godparents for the newborn of a mutual friend and soon began dating. “Well, we didn’t really date,” Mom said, “We didn’t go anywhere. I would go to church to the rosary every day, and your tata would come see me there after.”

Like Apá, Tata drank too much. His own sisters, our Tías Rosa and Ventura, both in their early twenties at the time, shared that information with Mom the afternoon the three crossed paths outside of Mom’s neighbor’s house. Ventura, the youngest in the family, took the lead. “He’s an alcoholic,” she said, “If you’re thinking of marrying him, you should know that.” An altruistic warning? Mom thought so, until she moved in with Tata weeks later and experienced Ventura’s possessiveness toward her brother, her jealousy, and her rage. That had been her first attempt, Mom would realize, at keeping Mom at bay.

Mom and Tata had only dated for a few weeks when Tata invited Mom to his family’s place on South Seventh Street after evening Mass. He and his sisters had inherited the property nine years earlier after their parents had died of cancer only a few months apart. Tata led Mom to believe that he, Rosa, and Ventura would host her. The three would chat for a bit before he escorted Mom back to her house. But no one was home when they arrived, as Tata already knew, and he took advantage of the opportunity to seduce her.

The three-room shack had just become her new home, she realized, lying in bed in the living room with Tata after he had taken her virginity. Her family’s Catholic moral code burned in her mind: If a woman gave in to a man’s advances and had premarital sex, she had to marry him to make it right. Even after Tata’s sisters arrived and demanded he take Mom back home, chastising him for having sex with such a young girl, Mom insisted that she couldn’t go back anymore. Her parents wouldn’t want her there after what she and Tata had done. Tata chimed in, saying he had no plans to return his girlfriend to her family. She would be living there with him from now on. Which is not to say that he was proposing. For a couple of months, he resisted marrying Mom, which confused and stressed her out. She wondered why he had had sex with her, then. And why did he want her to stay? Who knows what Tata was planning. Maybe to make Mom his permanent concubine.

The morning after Mom spent the night with Tata, Amá, stormed over to his house, knowing exactly where to find her daughter. “¡Cabrona!” she yelled at Mom, “¿No te da vergüenza?” Mom hung her head and sat there quietly, in jeans and a short-sleeve blouse Tata had made Tía Ventura lend her. Mom hadn’t brought a change of clothes with her the previous night, unaware she’d be moving in permanently. Yes, she was very ashamed of herself, she answered Amá in her mind. But what could she do now?

“The two of you have to get married,” Amá said, slamming the door on her way out.

After a week, Mom walked over to Mr. Hunter’s studio to return the keys because Tata forbade her from continuing to work. Out of jealousy, Mom said. “He wanted to keep me in the house so no other men would look at me.” Her former boss was furious at her. She had left him in a complete bind, he said, and made his retirement less certain now. It didn’t sway Mom, though. Tata had put his foot down, and she felt obligated to obey the man she already considered her husband.

Mom tried to settle into her new life, but from the start, Ventura despised her. Seething at the intrusion, she confronted Mom the morning after her arrival, after Tata had gone off to town for several hours. Ventura got right in Mom’s face and snarled that she wasn’t welcome in her home. “Get out of here now,” she told her. Mom tried to explain her predicament to Ventura again while reminding her that Tata did, in fact, want her there. She hoped Ventura would understand.

But Mom’s response didn’t placate her. It steamed Ventura even more. She lashed out anytime Mom tried to carry out any traditional wife duties, even a couple of months later, when Mom and Tata went to the courthouse and made it official. “It felt so wrong to sit around doing nothing,” Mom said. “It was my responsibility to do things for my husband and to help out, at least a little bit.” She also hoped to create a space for herself in that little home, to belong, especially now that she and Tata had married.

But Ventura continued to obstruct her. “I’m the one who takes care of him,” she told Mom. She’d block Mom’s path if she approached the stove to make dinner for her husband and snatched the dish towel out of Mom’s hand when she tried to help Ventura dry the dishes. One day, she grew so incensed at Mom’s repeated attempts that she scratched her forearm. Mom swore at Ventura and shoved her, which led to Ventura scratching up Mom’s arms even more and slapping away at her face and body, her rage at the intruder fully unleashed.

The two women fought regularly for the five years Tata’s sisters continued to live with the couple. And Tata would side with Ventura, Mom said. He’d accuse Mom of provoking her and allowed her to rage at Mom. It made Mom furious, so much so that after yet another fight with Ventura, Mom screamed at her, “You want your brother for yourself, don’t you?! Well, take him then!” Tata clutched Mom’s arm and yanked her toward him. He slapped her across the face for that comment. “You have a filthy mind,” he said.

“But what else was I supposed to think?” Mom told me. “God forgive me, but I really do think she was in love with him.”

To an extent, the arrival of children reduced the tension between Ventura and Mom, given that Ventura loved her brother’s children as if she had given birth to them herself. But it also spurred on more friction. Ventura’s possessiveness toward Tata began to extend to his children, especially when it came to Mom’s first born, Joe. “She wouldn’t let me take care of him,” Mom said. “She wanted to be the one to carry him and feed him and put him to bed. Like she thought she was the mom. Your tata was the dad, and she was the mom.”

Eventually, Mom reached her limit and gave Tata an ultimatum, emboldened, she claimed, by comments Tía Ventura had made one day. Tata and Tías’ parents had left the house to their son when they had died, not their two daughters. They expected the girls to marry and move in with their husbands and for Tata to continue living there with his own wife and kids. Suddenly, Mom saw a clear path to fending off Ventura and making her homelife saner. She could make Tata kick his sisters out, and the women couldn’t refuse.

After one final skirmish with Ventura, Mom told Tata, “We can’t keep living like this. Either your sisters go, or my kids and I will.” Tata made Tías leave but resented it for the remainder of their marriage. Tía Ventura and Tía Rosa also harbored a grudge toward Mom because of it for decades.

Although Mom expected her marriage to improve now that Tías no longer lived with them, Tata continued drinking and couldn’t hold down a job. Without Tías’ income, the family plunged into poverty. “My kids would say they were hungry and wanted a tortilla,” Mom said, “but some days we didn’t even have that.” And the more the family struggled financially, the more Tata and Mom fought.

“Why didn’t you just leave him?” I asked her when I first heard these stories. She had tried, she said. Twice. She moved out with her children and went to work as a waitress, but, each time, found she couldn’t afford to pay rent and utilities, hire a babysitter, and feed her family on her limited income. On top of that, Tías Ventura and Rosa threatened to take her children from her if she didn’t go back to Tata. The sisters had grown fully attached to their brother’s kids. Mom had no right, they believed, to take the kids away from them.

After a few weeks, Mom broke down and went back to Tata, figuring that, by living with him, she, at least, wouldn’t have to pay rent. After her second return, she applied for food stamps and welfare, something she had resisted out of pride. It meant admitting publicly in that government office downtown that she had an alcoholic husband who didn’t support her and her family. For years, she had also believed she could change him. But that had proven impossible, and her kids were suffering the consequences. The humiliation of having to ask for assistance made her even angrier at Tata, and she took to striking him with whatever she had in her hand anytime he grabbed her during their fights. One night, she shattered a baby bottle over his head, which sent him staggering to his sisters’ house for help in removing the shards of glass in his hair. Mom even tried locking him out of the house and forcing him to go live with his sisters. If she couldn’t leave, he should. But Tata broke the flimsy locks, which outraged Mom even further. It made for near constant fighting inside the cramped space.

Animosity erupted outside in the yard as well, but not only between Mom and Tata. For almost her entire seventeen years of marriage to him, Mom also clashed with an old drinking buddy of his who lived next door. Twenty years Tata’s senior, she was an obese woman named Santos, a name I found jarring the first time Mom told me about her. How could someone with the name “Saints” behave like such a vicious witch? Wouldn’t “Diabla” or “Bruja” make more sense? Because of Santos deeply dark skin, folks called her “La Cuerva,” the feminized version of “el cuervo,” the Spanish word for “crow.” La Cuerva was married—to a short, skinny man she terrorized and periodically beat—but she was in love with her younger neighbor. During the early years of Mom and Tata’s marriage, when she still had permission to come over in the evenings to drink with him and Tías, she’d sit on the bed and pull up her dress to expose her fat thighs, while Mom shook her head in disgust. “Qué asco,” she said. “And in my own house.” La Cuerva also leveled jabs at Mom, calling her a prude and ridiculing her frequent bathing and distaste for drinking and smoking. Fed up finally, Mom forced Tata to throw her out, and she forbade La Cuerva from ever coming over again.

This stoked La Cuerva’s hostility. At every opportunity, she punished Mom, mocking and insulting her as the two women did their chores outside. She also claimed that Tata, who now went over to her house to drink, was sleeping with her. “But I wasn’t the jealous type,” Mom said. “He could do whatever. I was too busy taking caring of my kids.” And since La Cuerva failed to get a rise out of Mom that way, she went after her children. Through the years, she hoarded my older brothers’ footballs and baseballs that inadvertently landed in her yard, sicced her German Shepherd on them, and called all of Mom’s kids “tuberculosis-infected.” She even threw rocks at the older kids, Mom said, and drenched her toddlers--my brothers Tino and Jesse and me--with her garden hose.

(Oddly, I don’t remember any of that. In fact, for some reason, I don’t have a single memory of that family living next door to us, although Mom’s stories about them would haunt me for decades.)

All of it infuriated Mom to the point of obscenity-riddled, threat-filled screaming matches with La Cuerva—and a few of La Cuerva’s kids, who soon took to backing up their mother during the arguments. Then, one summer evening, in the middle of yet another heated altercation, La Cuerva and one of her heavyset, teenage daughters, Marcela, stormed into our yard and shoved Mom onto the ground. They pinned her to the oversized cement slab that served as the front entrance to our home and slapped her, pulled her hair, and bit her hand when Mom freed her arm and got in a slap herself. Tata was out getting drunk, as usual, so he couldn’t stop them, although who knows if he actually would have. When he got home late that night, Mom frantically recounted the details, plunging her pinky inside the bottle of rubbing alcohol in her other hand. Her finger throbbed from Marcela having gnashed it with her teeth. But Tata blamed Mom. “You don’t know how to keep your big mouth shut,” he told her.

Before Tata’s arrival, Mom had spent a couple of hours in jail. The neighbors called the police when the fight broke out, and both she and La Cuerva were arrested. Mom was released after Amá enlisted the help of a lawyer in town whose house she cleaned. He drove into the neighborhood and asked various neighbors about the constant fighting, Mom discovered later. They all pointed the finger at La Cuerva and her family as the instigators of the conflicts. He made that case to the judge, who ordered Mom’s release. Mom doesn’t know whether La Cuerva was fined or just warned, but whatever the consequence, it restrained her and her daughter from physically going after Mom again.

But the arguing out in the yard didn’t stop completely. It continued on-and-off until a couple of years later when La Cuerva and her family lost their home. They couldn’t afford to live there anymore and had to move away.

“Just like your tía Ventura, La Cuerva put me through hell,” Mom said, when she shared the story with me for the first time. “All that was left was the hell I lived with inside our house back then, with your tata drinking all the time and never supporting the family.”

“But I’d go through all of it again,” she told me. “I’d live my whole life all over again to have all of my kids.”

That’s crazy, I thought. Why would anyone relive such a hard and horrible life?

And yet that’s exactly what I did, for many years, by asking her to repeat her stories and then obsessing over how outnumbered, overpowered, and abandoned Mom must have felt all of the time. Even in high school, I asked Mom to share the graphic details with me again. Why? Due to some unspecified trauma? Or a relentless drive to record them one day? Or maybe a very fragile sense of a separate self. As a closeted gay boy with no meaningful experiences of his own, did I ache to make those anecdotes mine so I could finally have a story? Or perhaps I hoped they would end differently after yet another recounting, that Mom and I would happen upon an overlooked detail that shed vegetative light on the barren terrain of our past. And that this would shift the course of the stories to come.